In this article we explore how there are many smaller risk

patterns that intermingle with each other, to provide some of the larger risk

behavior we might fear. For example,

there are many ways for the market to drop -6% in a short-period of time. Some examples include:

* -6% in a single-day

* -3% in a single-day, then -3% the following day

* -2% in a single-day, then -4% the following day

* -4% in a single-day, then -2% the following day

Looking at any one pattern and not the collection would be misinformative, as these patterns are also not haphazardly arriving over time. They rather work in conjunction with one another.

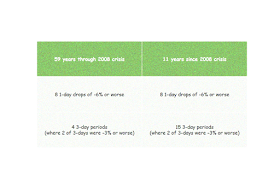

For example, we saw the same number of -6% down-days in the 59 years to 2008 global financial crisis, than we saw in just the 11 years since mid-2008. 8 days in each of the two time periods, though the latter length of time

was much more brief (and we are still in it!) And while we saw more -3%

down-days in the 59 years to 2008, then in the 11 years since, we did see more

consecutive -3% (or worse) down-days in the latter period. And the back-to-back nature of the risk events matter, as we'll note below.

Now we might eventually deliberate that we still had (to some degree) a higher concentration of risk even at the -3% level, since the start of the financial crisis. As the many broad market risk measures came generally more frequently in the heightened volatility era. Indeed in the past 11 years we also had more 3-day periods where two of the 3 days were -3% or worse, versus in the 59 years prior to mid-2008. 15 versus 4, as shown below.

The problem is it is still not that noticeable; the end of a 3-day period that looks like (-3%, +3%, -3%) will not cause people to think they suffered much of a loss. Because these fat-tails partially cancel. But change their ordering of days to say the following 3-day period (+3%, -3%, -3%) and we'll have people confused about how they may have suffered a -6% loss (from two days earlier). Again because of the serial nature of the -3% days.

Of course both 3-day periods above had the same 2 -3% days and 1 +3% day ingredients, yet the permutation of how those days were sequenced matters. Theory suggests it is to be random over some time frames, but it is not. And makes a large difference to those cognizant of how their smaller losses can still accumulate en masse.

There were in fact a higher portion of these back-to-back -3% days in the less intense 59-year period leading to the financial crisis. And this portion of about 50% is far less than the theoretical amount you would expect based on independence of returns (or we’d except 2/3 of the 3-day periods to be back-to-back).

Now we might eventually deliberate that we still had (to some degree) a higher concentration of risk even at the -3% level, since the start of the financial crisis. As the many broad market risk measures came generally more frequently in the heightened volatility era. Indeed in the past 11 years we also had more 3-day periods where two of the 3 days were -3% or worse, versus in the 59 years prior to mid-2008. 15 versus 4, as shown below.

The problem is it is still not that noticeable; the end of a 3-day period that looks like (-3%, +3%, -3%) will not cause people to think they suffered much of a loss. Because these fat-tails partially cancel. But change their ordering of days to say the following 3-day period (+3%, -3%, -3%) and we'll have people confused about how they may have suffered a -6% loss (from two days earlier). Again because of the serial nature of the -3% days.

Of course both 3-day periods above had the same 2 -3% days and 1 +3% day ingredients, yet the permutation of how those days were sequenced matters. Theory suggests it is to be random over some time frames, but it is not. And makes a large difference to those cognizant of how their smaller losses can still accumulate en masse.

There were in fact a higher portion of these back-to-back -3% days in the less intense 59-year period leading to the financial crisis. And this portion of about 50% is far less than the theoretical amount you would expect based on independence of returns (or we’d except 2/3 of the 3-day periods to be back-to-back).

say there have been 15 3-day periods, where exactly 2 of 3 days were a drop of -3% (or worse).— Statistical Ideas (@salilstatistics) June 29, 2019

if ordering is random, then in how many of these 15 periods would the 2 days be back-to-back?

NOTE more 💡 posted today on https://t.co/xq8nZhhu5V

cc @jben0 @nntaleb @ritholtz @pgogoi

Of course if we observe lower down the risk-spectrum (at say -2% down-days), we see that while there were more back-to-back -2% down-days, there was also a higher portion of back-to-back -2% down-days in the previous 59-year period. And again this portion is still far less than the 2/3 one would expect from theory.

We also had many more 3-day streaks of -2% or worse days. A lesson here is that if the -2% risk followed the storyline from the -3% and -6% tail-risks we described above, then the past 11 years would have seemed much more volatile. Due to the short-term impact of the -2% days being clustered together instead of more independently distributed.

What does this all imply about the future? It implies that we can not merely study fat-tailed drop patterns (here, here, here) in isolation. As if they happen independently of one another, or even assume the sequence within short-times are independent. We surely expect that over time, we might get accustomed to more convolutions of the smaller-risk levels (say -3%) versus the higher-risk levels (say -6%). But we may also see a higher blend of more -2% days, streaked together. And recall 3 -2% risks in a row would see a market drop of about -6%. Just happens at the end of 3-days however, instead of visible within a single-day.

FINAL NOTE: or the holidays, friday i’ll lower the price of my statistics e-book to $1/£1 (vs $8/£7). last promo was 2017; in 2015 it was a top-ranked school book. hope you read it & share a review. a.co/aFRDeIx

also will have a new color product (no formulas!): later this year.

No comments:

Post a Comment