Reminder we can now be followed on Twitter (@salilstatistics).

As markets glide up against new highs, there is debate about whether "this time" the markets will break through to an even higher plateau. It is interesting for quants and probabilists to understand the rare likelihood for an additional surge in risk-taking, despite being at already lofty levels. As it is we often hear that it is difficult to know where the top of the markets are, until after it has passed. Surges from very high levels of complacency sure are rare though and, we have not seen it since June 17, 2014. Then the S&P closed at 1942, hovering within a percent of its then all-time high (1951) made nearly a week prior. Today we are within 2% of the 2131 all-time high. On that June 17, the VIX was 12% (around the lowest, multi-month range seen since the global financial crisis). Yet instead of volatility that traders had positions for, the market collected further steam in each of the next three days! Setting new records of S&P 1957, then 1959, then 1963. The markets would continue a steady melt-up still, over the next 9 days of "risk on", until finally blowing off at 1985 (followed by a welcome relief for any surviving bears.) Through the vantage of the VIX, we see highlighted in blue on the chart below that the day after June 17, it plummeted 1.5 percentage points (from the 12.1% we described above, to 10.6%.) So it shouldn't take a lot to convince you that if all this happened from a VIX of 12%, then it could certainly happen in today's market where the VIX is in the 13's, as the VIX level has been many times throughout the past month. So tread with caution! The roller coaster's small ups-and-downs can force mistakes, since you don't know as they happen if you are in the coaster's smaller up-and-down hills versus the larger up-and-down mountains. Neither do active managers for any asset classes anywhere (see this article used for a talk at University of Cambridge later this month). If we do have a market spike higher in the near-term, it could wipe out the psyche of many traders who are confidently positioned (early but incorrectly) for a near-term top in the markets. In this article we will explore the dynamics of markets being erratic near a top, and how frequently and in what way they can surge higher even from near record territory, as opposed to simply roll over as we often expect (since it is often but not always the case). Much later in the future we'll complete a sequel article mixing together the opposite dynamic that we have written about before, of markets collapsing further, during a period of high tail-risk.

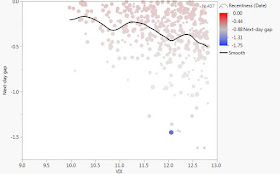

To lay some background probability data, see this chart immediately above. There are 6600 trading days in the history of the VIX. Of this, there are ~990 days (the frothiest 15% or 1.5 deciles trading days) where the VIX closed <12.8%. Of these, there were 437 days where the VIX closed the following day at an even lower level. These 437 "gap down" days (using the term gap to reflect surprise on volatility (or "gap up" in risk-taking) are plotted above relative to the prior day's closing VIX (horizontal axis). The size of each data represents how many days ago this data point represents: larger for today; smaller for just over a

¼ century ago!

We can see from the disturbances in the "smoother" that it is not always clear what is the probability of having beyond a -1 percentage points (pp) change, even as the VIX moves within these low levels. For example even as the VIX falls below the current level of 13s, the VIX can a small amount of times still have a 1-day drop down beyond 1pp on the VIX (or in this case leaving us with a VIX in the 12s or lower!) Incidentally 1pp is the amount of the typical VIX drop when it drops on a day. It can be used for a comfort gauge for active traders who are not generally aligned with (and not leveraged equal to) the market.

We can instead think about our data in the visual below. Where we group the VIX into equal sized partitions (and rounded down to the first decimal). And within each of these 5 we show the portion of the 1-day down days on the VIX within 1pp (in red) and beyond 1pp percent (in blue).

We see that this signal is fairly trendless, for the risk of a beyond a 1pp drop in risk-aversion when the VIX is <12.8%. Each VIX partition above is ~90 days so there is a sufficient sample, and each one we see has an about >95% probability of any next-day drop in VIX being a manageable within 1pp. The probabilities move though, similar to the smoother further above, indicating for example that the risk of a drop beyond 1pp is larger when the VIX is just <12.4% versus just >12.4!

So to better appreciate this overall risk of being mightily short and confident, but at precisely the wrong time, we need to see the amount of continued irrational risk-taking that occurs from any given low VIX level (prior to making a new higher level on the VIX later). This is a complex algorithm to execute but it's important to see. We show it below, using the same parameter values as the chart above.

The probability trend is now much clearer. The total drop in the VIX, from any of the shown VIX levels, becomes more limited to 1pp the further lower the starting VIX level is. When the VIX falls from a level of ~12.6%, 42% of the time it dropped beyond 1pp (and hence through convolution we know it can be great volatility in the VIX changes during this slide in the gauge). But when the VIX falls from just over 10%, only 9% of the time it dropped beyond 1pp. So further VIX drops are essentially the same even at these lower levels of VIX, but at the latter lower VIX levels the continued drops have a higher probability to be contained.

Combining this with the insights on the top charts, we see that the red bars in the chart above represent the total continued drop in the VIX -from the level shown on the horizontal axis-

that are limited to 1pp. And as the VIX falls below 12%, >85% of the entire future drop in the VIX is contained within 1pp. Those are simply the best odds available! On the other hand, if the VIX is in the 12s, then a lower 65% of the future VIX drop is contained within 1pp. In this latter case, there is simply greater risk for a short-seller that the market might move against them for a lengthier period than just 1-day. Given today's market levels in April 2016, this all suggests that markets can appear peak-like, and this is the likely bias. But there is still always going to be a need to understand the small probability (in blue on the chart above) that one should be more humble in their positioning, as there is still some chance that we can have continued higher peaks.

As markets glide up against new highs, there is debate about whether "this time" the markets will break through to an even higher plateau. It is interesting for quants and probabilists to understand the rare likelihood for an additional surge in risk-taking, despite being at already lofty levels. As it is we often hear that it is difficult to know where the top of the markets are, until after it has passed. Surges from very high levels of complacency sure are rare though and, we have not seen it since June 17, 2014. Then the S&P closed at 1942, hovering within a percent of its then all-time high (1951) made nearly a week prior. Today we are within 2% of the 2131 all-time high. On that June 17, the VIX was 12% (around the lowest, multi-month range seen since the global financial crisis). Yet instead of volatility that traders had positions for, the market collected further steam in each of the next three days! Setting new records of S&P 1957, then 1959, then 1963. The markets would continue a steady melt-up still, over the next 9 days of "risk on", until finally blowing off at 1985 (followed by a welcome relief for any surviving bears.) Through the vantage of the VIX, we see highlighted in blue on the chart below that the day after June 17, it plummeted 1.5 percentage points (from the 12.1% we described above, to 10.6%.) So it shouldn't take a lot to convince you that if all this happened from a VIX of 12%, then it could certainly happen in today's market where the VIX is in the 13's, as the VIX level has been many times throughout the past month. So tread with caution! The roller coaster's small ups-and-downs can force mistakes, since you don't know as they happen if you are in the coaster's smaller up-and-down hills versus the larger up-and-down mountains. Neither do active managers for any asset classes anywhere (see this article used for a talk at University of Cambridge later this month). If we do have a market spike higher in the near-term, it could wipe out the psyche of many traders who are confidently positioned (early but incorrectly) for a near-term top in the markets. In this article we will explore the dynamics of markets being erratic near a top, and how frequently and in what way they can surge higher even from near record territory, as opposed to simply roll over as we often expect (since it is often but not always the case). Much later in the future we'll complete a sequel article mixing together the opposite dynamic that we have written about before, of markets collapsing further, during a period of high tail-risk.

We can instead think about our data in the visual below. Where we group the VIX into equal sized partitions (and rounded down to the first decimal). And within each of these 5 we show the portion of the 1-day down days on the VIX within 1pp (in red) and beyond 1pp percent (in blue).

We see that this signal is fairly trendless, for the risk of a beyond a 1pp drop in risk-aversion when the VIX is <12.8%. Each VIX partition above is ~90 days so there is a sufficient sample, and each one we see has an about >95% probability of any next-day drop in VIX being a manageable within 1pp. The probabilities move though, similar to the smoother further above, indicating for example that the risk of a drop beyond 1pp is larger when the VIX is just <12.4% versus just >12.4!

So to better appreciate this overall risk of being mightily short and confident, but at precisely the wrong time, we need to see the amount of continued irrational risk-taking that occurs from any given low VIX level (prior to making a new higher level on the VIX later). This is a complex algorithm to execute but it's important to see. We show it below, using the same parameter values as the chart above.

The probability trend is now much clearer. The total drop in the VIX, from any of the shown VIX levels, becomes more limited to 1pp the further lower the starting VIX level is. When the VIX falls from a level of ~12.6%, 42% of the time it dropped beyond 1pp (and hence through convolution we know it can be great volatility in the VIX changes during this slide in the gauge). But when the VIX falls from just over 10%, only 9% of the time it dropped beyond 1pp. So further VIX drops are essentially the same even at these lower levels of VIX, but at the latter lower VIX levels the continued drops have a higher probability to be contained.

Combining this with the insights on the top charts, we see that the red bars in the chart above represent the total continued drop in the VIX -from the level shown on the horizontal axis-

that are limited to 1pp. And as the VIX falls below 12%, >85% of the entire future drop in the VIX is contained within 1pp. Those are simply the best odds available! On the other hand, if the VIX is in the 12s, then a lower 65% of the future VIX drop is contained within 1pp. In this latter case, there is simply greater risk for a short-seller that the market might move against them for a lengthier period than just 1-day. Given today's market levels in April 2016, this all suggests that markets can appear peak-like, and this is the likely bias. But there is still always going to be a need to understand the small probability (in blue on the chart above) that one should be more humble in their positioning, as there is still some chance that we can have continued higher peaks.

No comments:

Post a Comment